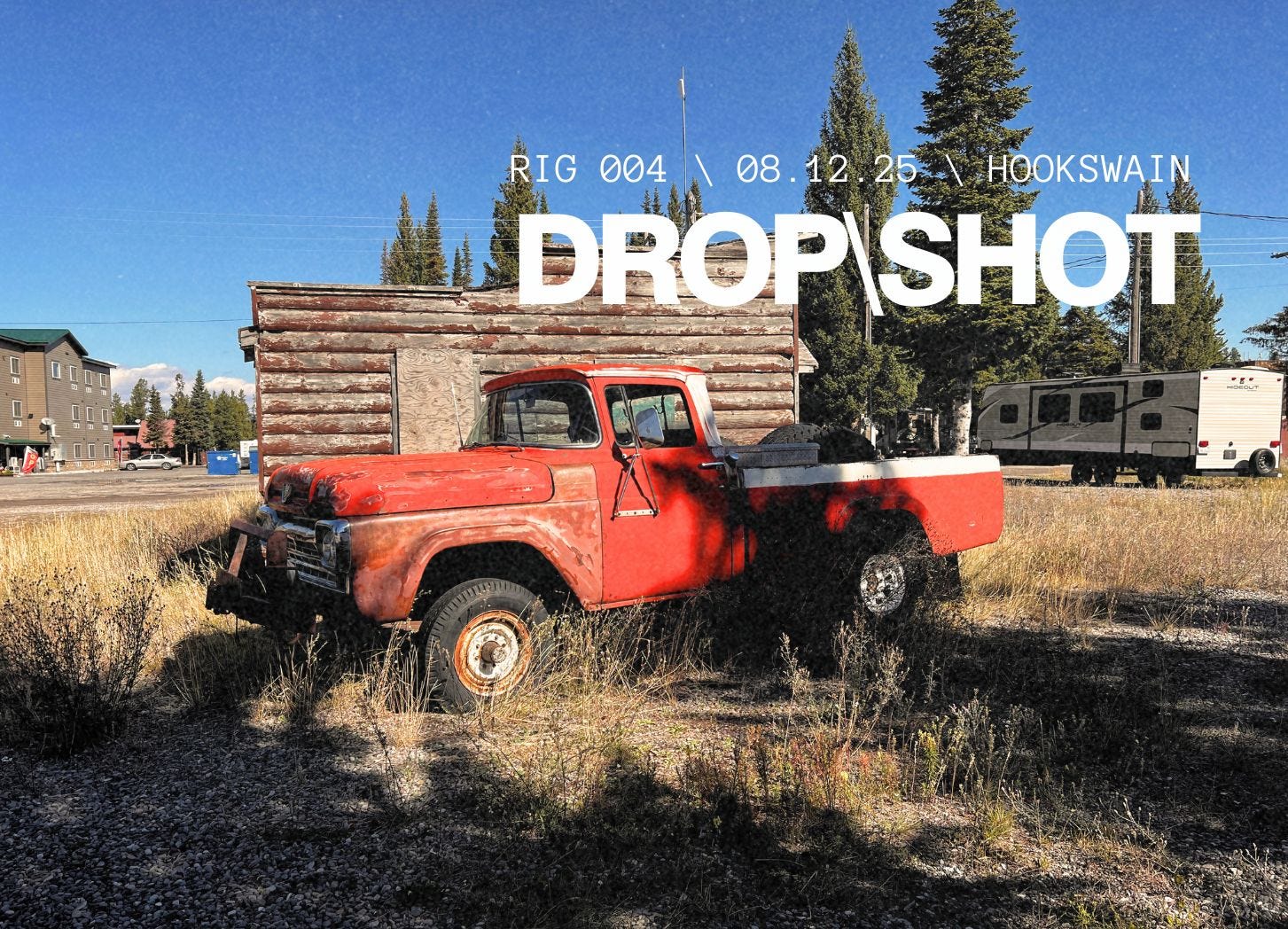

\\ Cover Story \\

Location: West Yellowstone, Montana

I snapped this late ‘50s Ford F-Series truck on my iPhone last September during my fortieth birthday trip to Yellowstone National Park. Something about it felt compelling — but haunting — as though this faded pickup and derelict cabin were the last vestiges of an era of the West I will never know.

Beware of Flying Ants

If you’re near water that remains fishable for trout throughout the summer, you may have found yourself stymied by an inscrutable hatch that for the life of you, you can’t seem to match. It’s maddening; trout rising in gleeful splashy takes yet avoiding even your most convincing trichoptera imitations. If you experience this, try tying on an ant pattern.

Now, let’s be clear. I am not referring to a black size eight Chubby Chernobyl or anything that even approaches the look and presentation of a hopper. The ant you want is small — size 16-18 — and should have distinct bulbous ends like a small dumbbell. Something like this:

You see, every summer, the Queen ant signals her male companions that it’s time to expand their species’ territory by flying the coop and setting up shop in a new location. Together they all sprout wings and swarm off, mating as they go. The males die shortly after mating and fall to earth, or, if the trout are lucky, river.

This “hatch” is impossible to predict; even entomologists don’t know what triggers a swarm, especially because the changes in rainfall, humidity and barometric pressure preferred by the colony can be hyper-local. The fleeting and unpredictable nature might explain why trout seem to zero in on ants when they are present, sometimes moving a great distance to snatch one.

Take my word for it; if you’re on a trout stream between Independence Day and Labor Day, beware of flying ants.

The Wild World of Dapping

I recently fell down a rabbit hole while researching the strains of Irish brown trout and found myself charmed by this video depicting an Irish fishing technique known as dapping.

Instead of a traditional cast, the dapping angler uses the wind to lift the line and deliver the fly. Very long rods — twelve feet and longer — help keep the line elevated off the surface of the water such that just the fly makes contact.

There is a version of dapping that exists in America, likely a relative of this style adapted from its original use on windy lochs to small streams and rivers. Here, the fly is lowered to the surface using the rod tip; again the line should not make contact with the water.

From what I can find, Don Miller seems to be (have been?) the expert on American-style dapping, with a 2014 book entitled Dapping. A Fly Fishing Technique: My Secret Method of Catching Large Dominant Trout.

Here’s an excerpt from the book description:

“His 40 years of learning how to catch that rare and elusive large, dominant, heavy-weight trout, [sic] that the ones very few fly fishermen ever catch, has been a never-ending pursuit– one that has caused him to endure many sleepless nights pondering: “If I was a large trout needing large meals to sustain life and energy, plus being cautious and wary, where would I reside?” Once I discovered the answers to that question, I concluded that dapping was the only method that would work. If you apply all the techniques and methods described in this book over time, you too will succeed.”

Color me intrigued.

Have you tried traditional or American-style dapping? If so, I’d love to hear about your experience. Email me at info@hookswain.com

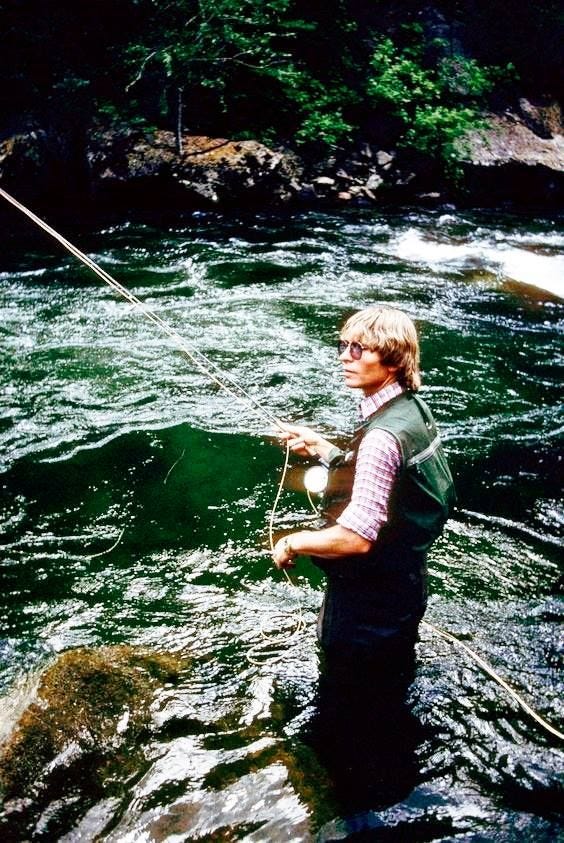

#senditwithstyle

This photo of devout fly angler John Denver knee deep in a run wearing a pink plaid shirt and matching pink teashades is the epitome of not taking it too seriously. Or that ‘Rocky Mountain High’ is more than just a hit song title.

A Fly in the Ointment

On summer evenings, the air above a river should be alive with small wings flickering in the slant light, mayflies lifting like ash, caddis skipping in erratic arcs. There should be a hum, the buzz of the river giving birth to a whole generation of insect life.

But lately, that hum feels muted. The sky over the water seems thinner, the hatches sparser, the night settling in without its usual chorus. It’s a quiet you can’t quite name until you remember what’s missing.

A May 2023 study led by Notre Dame biologist Jason Rohr concluded that insects are on the decline nationwide, confirming the warnings we’ve heard from anglers and amateur entomologists for decades. But as with most things, the study revealed that the change in biomass and biodiversity was far more nuanced than just simple decline.

According to Rohr, there has been a shift in the makeup of America’s streams and rivers in favor of more disruption-tolerant species. Less tolerant species have disappeared, allowing the more change-resistant insects to proliferate. The result is a growing homogeneity of insect life.

The study looked closely at differences between rivers and streams draining forested and grassland regions, and those coursing through urban and agricultural lands. The findings showed that the existing differences between those stream communities has only gotten wider suggesting that over the past thirty years, water running through urban and agricultural lands have gotten less biodiverse and populated with ‘weedy’ taxa capable of surviving in harsher environments.

In June of 2023, Tom Rosenbauer hosted stream ecologist Mike Miller on the Orvis Fly Fishing Podcast. During their nearly hour-long discussion, Miller articulated the effects of popular pesticide – neonicotinoids, or neonics – on aquatic ecosystems. Miller’s research focused on waterways in Minnesota and revealed that not only is the dangerous neurotoxin being widely used, but that the effects of its use might just be materializing.

Neonics, explained Miller, are synthetic compounds similar to nicotine, and are highly toxic to insects. They operate by binding permanently to neural receptors in insects, overstimulating the insect’s nervous system, leading to uncontrolled nerve signals. This overstimulation causes paralysis, followed by death.

Chemical companies have now started coating seeds in an attempt to introduce the toxin even earlier in the process. According to a 2021 study, “abrasion of the seed coating generates insecticide‐laden planter dust that disperses through the landscape during corn planting and has resulted in many “bee‐kill” incidents in North America and Europe.”

It seems a sad truth that neonics and widespread insect decline are connected. What’s worse, we’ve been here before. Rachel Carson saw it coming in 1962, when Silent Spring warned that our chemical ingenuity could just as easily unmake the natural world as improve it. Back then, it was DDT and the robins that vanished from suburban lawns. Today, it’s a quieter crisis, happening in the water, measured not in the silence of birds but in the absence of hatches and the sameness of the insects that remain.

For anglers, the change is as much felt as seen: fewer mayflies lifting from the surface, fewer caddis dancing in the evening light, and the creeping sense that a river without its full chorus of insects is a river diminished. Carson called it a “silent spring.” If we’re not careful, we may find ourselves wading into a silent current.

Very little research has been conducted to clearly define the effects of compounds like neonicotinoids on non-target species within various trophic levels of these ecosystems (not surprising...). It's a startling domino effect that I recall being discussed over a decade ago within the entomology community, and one which garners greater amplification.

Think I saw that same pick up a few years ago on a week's worth of breakfast runs at Ernie's.